American Robin

Turdus migratorius

The American Robin is the quintessential ‘Bird of Spring’ for most of North America, but we’re lucky enough to have them as year-round residents on eastern Vancouver Island. They’re common almost everywhere but are especially visible after rain (so, yeah, mostly in the winter months) chasing down worms that wriggle to the surface to avoid drowning in the soaked soil. They have a gentle call and a sociable nature, preferring to roam in flocks (almost herds at times), but will scold you if you get too close.

Anna’s Hummingbird

Calypte anna

I first moved to the West Coast in the winter, and while exploring the Lower Mainland’s waterfront one day in January I came across a truly unbelievable sight—a hummingbird in a tree! I couldn’t believe my eyes. I figured this poor little thing had somehow gotten caught up in a storm in California and blown north, which seemed an unbelievable journey for such a small and delicate creature. But of course, we West Coasters know an even un-believabler truth; these perky creatures are year-round residents. I’ve taken photos of them in raging snowstorms, sipping perkily on the sugar blend in my feeders, and I recently found out that local birds are even choosing to BREED in the winter, presumably to reduce competition from their territorial summer humming-mates, the Rufous Hummingbirds. They originally only overwintered on the Baja California Peninsula and Southern California, but the slow and steady march of exotic ornamental plants and willing feeder-fillers northwards has allowed them to spread their incredibly small wings and capitalize on an incredible opportunity.

For more, please read Anna’s Hummingbird on Wikipedia.

Bald Eagle

Haliaeetus leucocephalus

The bald eagle is an iconic bird of the Canadian West Coast, although its range essentially encompasses all of Canada and the United States, outside of the Arctic tundra. Their population density is highest on the coastal Pacific, due to the incredible variety of easily accessible food, and they tend to concentrate near known salmon runs in the winter months…although they seem to be found at their highest density near the Cedar Dump. They’re not dumb. They know what’s there.

Barred Owl

Strix varia

I’m about 60% certain the above owl is a Barred Owl. The only photo I have is from directly beneath an owl perched on a power line, and it’s not very flattering. The WordPress royalty free photo service’s search function for specific birds is…challenging, to say the least.

The barred owl has about the most distinctive call you could imagine—the quintessential ‘who cooks for you?!’ you’ve probably heard in the distance as the sun sets (or, more alarmingly, from directly overhead and the cats are still out).

They’re a large owl, native to eastern North America and generally considered invasive here on the West Coast. Invasiveness is a difficult thing to measure sometimes—typically if something is introduced by mankind and outcompetes the local species, it’s an easy call. But the Barred Owl is a tougher nut to crack…it came here all by itself, enabled by our unfortunate ability to wittingly and unwittingly change the landscape around us as we settle. The straw that breaks the camel’s back in this case seems to be that they also handily outcompete our local owls, such as the Burrowing Owl.

Bewick’s Wren

Thryomanes bewickii

These cheerful little birds are easy to hear and difficult to spot, sharing the usual wren traits of flitting quickly and noiselessly from branch to branch while seeming to scold you from 12 directions at once. They’re fairly ordinary looking but are full of character, being especially curious in the early spring while they look for a spot to settle down and nest. I’ve come across their nests in a variety of unlikely locations, but my favourite so far has been in the eaves of my shed, nestled into the insulation. One of the reason they’re less known is that they’re obligate insectivores—you’re not going to see these at your seed feeders, unless the seed feeders happen to attract large numbers of bugs (in which case you should probably get that checked out). Nonetheless, I find their antics make them one of the most enjoyable yard birds to observe, particularly when they arrive with a beak full of spiders.

For more, read Bewick’s Wren on Wikipedia.

Bushtit

Psaltriparus minimus

The bushtit commonly adheres to the Milford School’s mantra of being ‘neither seen nor heard’. On the rare occasions you do notice a flock, it’s usually little more than a bit of an extra rustle in the leaves of a nearby bush, or maybe a very quiet peeping if you’re really paying attention. They’re very plain looking and flit quickly between the branches searching for ants and other small bugs to eat. And if you’re really, REALLY paying attention, you might spot their very distinctive nests high in the trees or bushes; it resembles a pendant, built with moss and lichen, assembled with spider silk, and lined with the bird’s own feathers.

Southern BC is actually the very northernmost tip of the bushtit’s range, but they can be found all the way south to Guatemala and southern Mexico.

Read more about the American bushtit on Wikipedia (they’re the only New World bushtit, so we omit the ‘American’ part for brevity).

California Quail

Callipepla californica

The California Quail is one of my favourite birds, if for no other reason than its perfectly ridiculous plume. They’re year-round residents on the Island, though their behaviour changes radically throughout the season. As I type this in the spring, the quail have paired off and can be found two-by-two while they accomplish their courtship, mating, and nesting. Typically in the early summer they’ll take a page from the bushtits and be ‘neither seen nor heard’ while they raise their chicks hidden deep in the brush, but come late summer they’ll emerge with their fully mobile chicks and join together into much larger groups, often twenty or thirty strong. They’ll remain like this through the fall and winter, staying in their large groups until the spring comes again.

I had a covey of quail who decided to settle into my lilac bushes for the winter, and it gave me great excitement to see them swing by my ground feeders (and the ground under my non-ground feeders) as part of their daily circuit. Alas, the excitement was short lived, as what started off as a group of ten seemed to dwindle by one or two birds per week, getting smaller and smaller as December ground into January. By early February, only two birds were left, and I was confused—why did the others leave? Watching from my basement window one day, my question was answered—the remaining two were flushed from their ground feeder by a very plump looking Sharp-shinned hawk. After that, one remained—and she, only for a week. So ended my winter with the quail.

Canada Goose

Branta canadensis

As a pilot, I have a very conflicted experience with Canada geese. On the one hand, they’re loud, gather in large groups, poop everywhere, and are known to be somewhat ornery when approached. On the other hand, they fly into airplanes with somewhat alarming regularity. So that’s…well, I guess that’s not very conflicted.

Many Canadian cities struggle with large number of Canada geese—Toronto and Montreal in particular have seen an explosion of the geese in their downtown parks, with all their concomitant issues. Vancouver has a similar issue, but with snow geese, and only in the spring when they stop in for a nibble in Richmond winging their way north to the Arctic. Here on the Island, we’re just far enough off the western flyway that we have neither of these issues, for which we are mostly thankful.

That said, we do have a fairly healthy population of Canada geese resident throughout the year. I’m just now in from mowing the lawn, and one of these geese in particular took a disliking to me encroaching on his territory (read: my lawn). Hissing ensued, and then I got to mow through a large pile of goose poop. It was delightful.

Cedar Waxwing

Bombycilla cedrorum

The Cedar waxwing, in my eyes, is one of the most beautiful birds we have here on Vancouver Island. Despite their bright plumage, I really only notice them in late spring, when the cherry trees are bursting with fruit and large (10-12) flocks of waxwings wing out of nowhere and begin to gorge. I’ve heard they’re far less common in built up areas, but in our part of the world, if you have cherry trees, you’ve probably experienced the waxwings. (Alternatively, if you’ve noticed many of your fruit have small triangular beak-marks removed, then you’ve DEFINITELY experienced the waxwings).

Chestnut-backed Chickadee

Poecile rufescens

My first experience with this west coast chickadee was while visiting a friend in Vancouver. Walking through Stanley Park, I found myself being followed quite closely by a bird resembling the black-capped chickadee I knew from Ontario, but not quite. It seemed very inquisitive, and on a whim I held out my hand to see what it would do. It cocked its head, seemed to think for a moment, and then flitted over and perched on my finger for a few seconds before flitting away again. Our eastern birds were MUCH ruder than that. I was instantly in love. It wouldn’t be a huge stretch to say that this one experience played an outsized role in convincing me to move here. And I’m happy to report that Vancouver Island’s chickadees more than rise to the level of their mainland counterparts—if you’re out for a hike, visiting a friend’s house, or even just see one near you feeder, try holding out your hand—you might be in for a delightful experience.

Common Raven

Corvus Corax

The common raven is simply one of the most impressive birds you could ever hope to meet. I can’t even hope to describe it myself, so I’ll just defer to the Wikipedia description.

The common raven (Corvus corax), also known as the northern raven, is a large all-black passerinebird. Found across the Northern Hemisphere, it is the most widely distributed of all corvids. There are at least eight subspecies with little variation in appearance, although recent research has demonstrated significant genetic differences among populations from various regions. It is one of the two largest corvids, alongside the thick-billed raven, and is possibly the heaviest passerine bird; at maturity, the common raven averages 63 centimetres (25 inches) in length and 1.2 kilograms (2.6 pounds) in mass. Common ravens can live up to 21 years in the wild,[2] a lifespan surpassed among passerines by only a few Australasianspecies such as the satin bowerbird[3] and probably the lyrebirds. Young birds may travel in flocks but later mate for life, with each mated pair defending a territory.

Common ravens have coexisted with humans for thousands of years and in some areas have been so numerous that people have regarded them as pests. Part of their success as a species is due to their omnivorous diet; they are extremely versatile and opportunistic in finding sources of nutrition, feeding on carrion, insects, cereal grains, berries, fruit, small animals, and food waste.

Some notable feats of problem-solving provide evidence that the common raven is unusually intelligent.[4]Over the centuries, it has been the subject of mythology, folklore, art, and literature. In many cultures, including the indigenous cultures of Scandinavia, ancient Ireland and Wales, Bhutan, the northwest coast of North America, and Siberia and northeast Asia, the common raven has been revered as a spiritual figure or godlike creature.[5]

In conclusion, big, smart, fast, widespread, long lived, godlike. Questions?

Common Yellowthroat

Geothlypis trichas

These beautiful little birds are commonly heard near ponds and lakes, living and collecting small bugs and flies among the reeds and grasses. They’re far less common in dry areas. You’ll probably recognize their ‘wickety-wickety-wickety’ call if you’re spent any time hiking near a marsh, but they’re fairly retiring and will leave quickly if they sense you nearby. I set up a small viewing platform with a lawn chair in a tree overlooking our small beaver pond and was rewarded for sitting still for long periods of time with the above shots, which I considered a win. My wife considered it all ridiculous.

Read more about the common yellowthroat on Wikipedia.

Dark-eyed Junco

Junco hyemalis

The Dark-eyed juncos took a while to grow on me when I first moved here—they’re pretty plain looking birds, and seem entirely too abundant in the fall and winter to really leap to the eye. But they’re surprisingly complex little birds—their plumage varies wildly across the species, ranging from dominantly black to containing little to no black at all. I’ve often seen strange looking birds at my feeders in the winter and have spent many minutes excitedly searching for my binoculars only to realize “it’s just another junco” once I get close up. They also have a very nice little song, being known within the birding set as an excellent bird through which to study ‘bird language’. I’m not QUITE at that level yet, but, you know…good to know.

Eurasian Collared Dove

Streptopelia decaocto

The Eurasian collared dove is, as you might guess, invasive in North America, and pretty much everywhere else on the planet too (but not Iceland, which says more about Iceland than it does about the Eurasian collared dove). Evidence suggests that they’re not overly damaging to their environment, nor do they tend to outcompete the local mourning doves, so their presence here merely…is. They’re fairly unremarkable, but they do tend to make some unexpected noises that’ll have you reaching for your binoculars and then disappointedly realizing “oh, it’s just a dove”.

Golden Crowned Sparrow

Zonotrichia atricapilla

I was actually thinking to myself, “You know, there’s not really much to say about the golden crowned sparrow—wait, I’ll check Wikipedia to see what interesting facts I can dig up to seem knowledgeable!” And Wikipedia in one line tells me…

The golden-crowned sparrow (Zonotrichia atricapilla) is a large American sparrow found in the western part of North America.

I feel less bad about my ignorance now. There is one small note, which is that the golden crowned sparrow is very similar to the White-crowned sparrow, which has (you guessed it) a white crown instead of a gold one. Apparently the lineage split very recently. My entry on the white crowned sparrow, it seems, will be equally short.

Great Blue Heron

Ardea herodias

You know how it’s a thing now that birds are modern day dinosaurs? Maybe you’d find that difficult to believe, up until you heard two Great blue herons yelling at one another. I KNOW what they sound like, and to this day hearing one nearby makes me nearly jump out of my skin and run for cover. They’re quite beautiful, beyond the noises they produce.

Southern Florida boasts a sub-population which is coloured entirely white, and is known as the Great white heron, which is kind of neat. Beyond that, Wikipedia tells me that we grow ’em large here in BC—our average heron is almost half a pound heavier than those found further east.

Try not to think about that next time one yells at you from a nearby tree or bush.

House Finch

Haemorhous mexicanus

The House finch seemed all too common and unremarkable to me to be worth much attention. Coming from out east, I had a variety of experiences with the similar but smaller purple finch, and kind of assumed the House finch was a large, duller, and less interesting version of my beloved Purple finch.

But MAN can these guys sing. The audio file doesn’t really do them justice (notwithstanding the bonus raven)—they have one of the most varied and interesting songs of any of the common feeder birds here on the Island. Wikipedia further tells me

Originally only a resident of Mexico and the southwestern United States, they were introduced to eastern North America in the 1940s. The birds were sold illegally in New York City[6] as “Hollywood Finches”, a marketing artifice.[5] To avoid prosecution under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918, vendors and owners released the birds. They have since become naturalized; in largely unforested land across the eastern U.S., they have displaced the native purple finch and even the non-native house sparrow.

So that’s kind of interesting. Honestly, any bird that can outcompete a house sparrow is ok in my books.

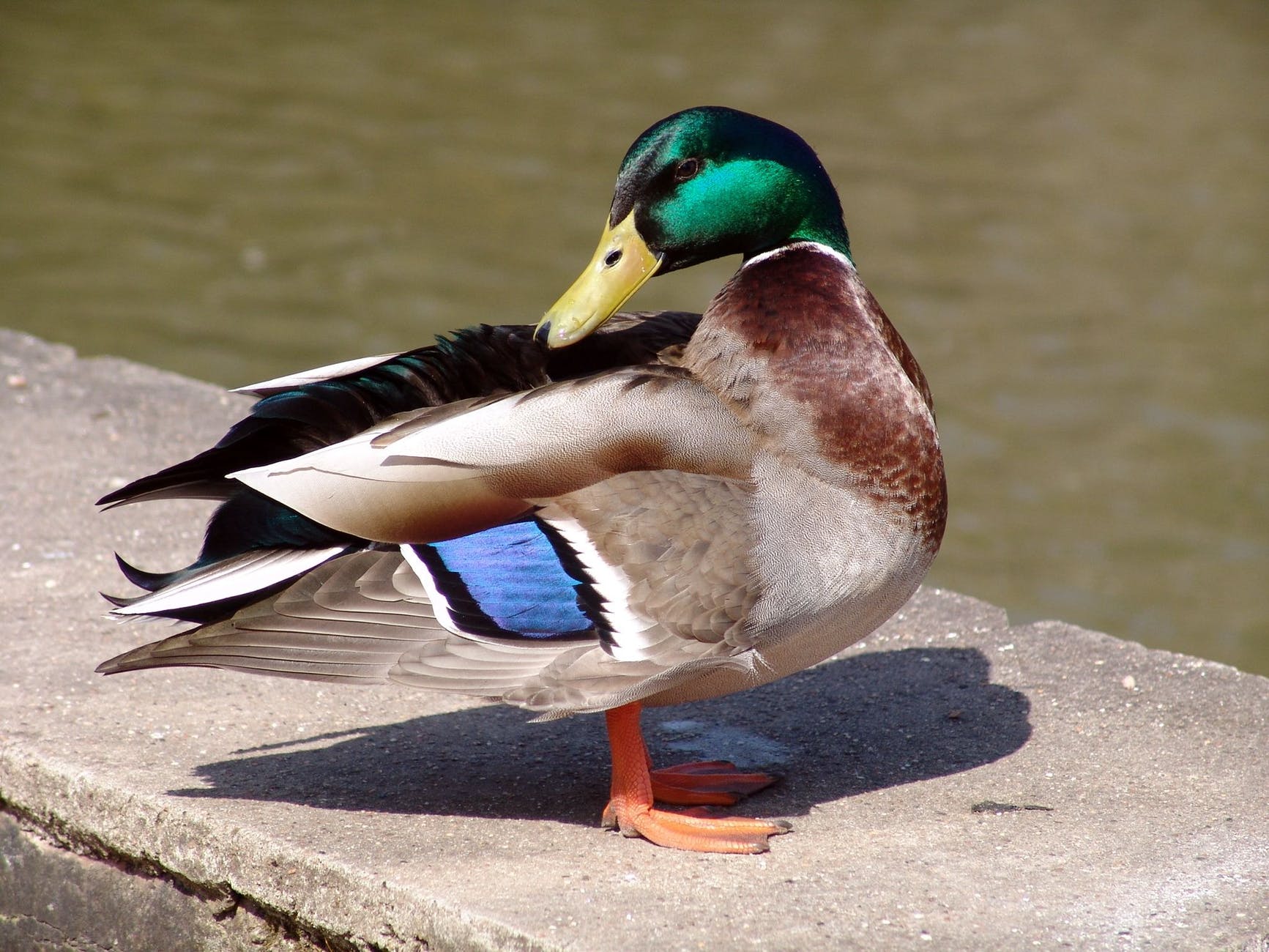

Mallard

Anas platyrhynchos

It’s a Mallard.

And here’s some video of mallards, by Mark from www.avibirds.com

Marsh Wren

Cistothorus palustris

The Marsh wren is another very common summer bird in local marshes and wetlands—chances are you’ve heard its distinctive chitter from afar as you hike nearby. Our very small beaver pond hosts three or four of them in our reeds, and it’s about as small as wetland habitats get. Like most wrens, they’re very entertaining to watch, and generally quite curious about interlopers, but I’ve never managed to get as close to one as I have to the Bewick’s. Also like the Bewick’s, their nests can be quite easy to find—you just have to watch the bird with binoculars for a few minutes and see where it concentrates its time.

Read more about the Marsh wren on Wikipedia—and be sure to check out the range map. I find it oddly beautiful.

Northern Flicker

Colaptes auratus

The Northern flicker is another of those local birds that I would describe as ‘weirdly beautiful’, not that my photo does it much justice (and searching the WordPress royalty-free image gallery for ‘Northern flicker’ returns three pages of aurora borealis and (for whatever reason) two blue-footed boobies, so that’s not much help). They live here year-round, although I’ve come to associate their screeching cries with the onset of fall. They’re virtually silent the rest of the year, but when the rain starts to fall—boy-o, that’s their time to shine.

Flickers are woodpeckers, as you’d come to know if you ever had one take a sudden interest in your eaves. Putting aside the somewhat alarming fact that they’re only there because you have tasty bugs in your walls, they can be fairly difficult to dislodge once they’re there—and they can do damage ranging from ‘why won’t he leave the chimney alone?!’ to ‘screw it, I’m just going to replace the entire wall’. Our friend in the BC interior had difficulty tracking down an odd knocking in her furnace, incurred two separate repair callouts, and finally had the guy come in while the noise was still occurring—he knew exactly what it was. She then invested in a slingshot and proudly told us later that it took her a while but she’d ‘gotten some feather’ and thought the episode at an end.

Our fingers are crossed.

Also, simply because it’s delightful—from Wikipedia:

Over 100 common names for the northern flicker are known, including yellowhammer (not to be confused with the Eurasian yellowhammer), clape, gaffer woodpecker, harry-wicket, heigh-ho, wake-up, walk-up, wick-up, yarrup, and gawker bird.

Northwestern Crow

Corvus caurinus

The Northwestern crow is a slightly smaller analogue of the American crow, which is why they are known to defend themselves with knives.

Pacific Wren

Troglodytes pacificus

I’ve only ever seen the Pacific wren in coniferous forests, and then only incidentally—they’re tiny, virtually noiseless, and about as flit-ty as they come. Wikipedia really says it best:

Its movements as it creeps or climbs are incessant rather than rapid; its short flights swift and direct but not sustained, its tiny round wings whirring as it flies from bush to bush.

Virtually poetic.

Pileated Woodpecker

Dryocopus pileatus

The Pileated Woodpecker is the second-largest woodpecker in North America, or even the largest if you (like most experts) consider the Ivory-billed woodpecker to be extinct. ‘Pileated’ refers to its bright red chapeau, but in far fancier terms, which is unfortunate when you think about it. Wouldn’t a black-pileated chickadee seem much more exotic?

Based on my personal experience, the best spot by far on the Island to spot a Pileated Woodpecker is on the telephone pole in front of my house. I’m assuming this means it’s full of tasty, tasty grubs, which I try not to think about whenever the wind is blowing.

Red-breasted Nuthatch

Sitta canadensis

The red-breasted nuthatch is given entirely short shrift by Wikipedia.

Its call, which has been likened to a tin trumpet, is high-pitched and nasal. It breeds in coniferous forests across Canada, Alaska and the northeastern and western United States. Though often a permanent resident, it regularly irrupts further south if its food supply fails. There are records of vagrants occurring as far south as the Gulf Coast and northern Mexico. It forages on the trunks and large branches of trees, often descending head first, sometimes catching insects in flight. It eats mainly insects and seeds, especially from conifers. It excavates its nest in dead wood, often close to the ground, smearing the entrance with pitch.

High-pitched and nasal?! I find the ‘meep meep’ of the nuthatch to be among the more calming of the songbird calls. It doesn’t hurt that the bird is just bursting with character, full of curiosity about its surroundings, poking pretty much every hidey-hole it finds for morsels of food, and seemingly defying gravity by hopping up and down vertical tree trunks facing whichever direction it likes. As for calling it a vagrant, well…I guess that’s fair. Vagrant in this sense just means that it shows up where it shouldn’t, which is a little judge-y, but you’d think the people on the Gulf Coast and northern Mexico would be delighted.

Anyways, count this among my favourite birds (there’s more than a few of them in this list I’ve called my favourite, I know, but I have a big heart).

Red Breasted Sapsucker

Sphyrapicus ruber

Have you ever been out walking and come across a tree riddled from root to canopy with lines of little horizontal dots? That’s this guy at work, drilling out the wounds in the tree to get sap flowing to the surface. Akin to a beaver, the sapsucker actually creates food and habitats for other creatures while going about its day.

A sapsucker’s tongue is adapted with stiff hairs for collecting the sap. Red-breasted sapsuckers visit the same tree multiple times, drilling holes in neat horizontal rows. A bird will leave and come back later, when the sap has started flowing from the holes. Repeated visits over an extended period of time can actually kill the tree.[3] The insects attracted to the sap are also consumed, and not only by sapsuckers. Rufous hummingbirds, for example, have been observed to follow the movements of sapsuckers and take advantage of this food source.[2]

That’s actually a pretty nice segue to the

Rufous Hummingbird

Selasphorus rufus

…which is, unsurprisingly, one of my favourite birds on the Island! I know, I know. I promise this one is the last one. The rufous is noticeably smaller than the Anna’s, but makes up for its small size by packing in three times as much personality. These birds are astounding migrants, making a circuit up to 3600 km long throughout the year. They show up here surprisingly early in the spring, often in late February or early March, and almost immediately begin their very distinctive aerial mating display. I’ve tried to describe it to friends and family in the east using a combination of hand motions and enthusiastic noises, but I always feel like I’m giving them short shrift—there’s only so much you can do with your hand to make it seem like a hummingbird’s rear waggling in mid air while you say ‘buh-buh-buh-BEW!’ over and over. I’ve tried to get a video of the tiny hummingbird moving at high speed from a hundred feet in the air in an parabolic arc curving towards wherever you are not, but that turns out largely as you might expect…so hand waggling and weird noises it shall have to be.

Once they’ve fledged their chicks, the whole kit and caboodle take off for the upland wildflowers as the summer wears on, meaning they’ve often left our little corner of the Island by mid July. They’ll follow these alpine wildflower blooms all the way back down to their overwintering grounds in the Mexican state of Guerrero (think Acapulco—not so different from the average Canadian).

I highly encourage you to check out Wikipedia for more on this incredible bird.

Red-winged Blackbird

Agelaius phoeniceus

I have a bit of a conflicted relationship with the Red-winged blackbird. They’re beautiful, yes, but we live near a small beaver pond that boasts a THRIVING population of these birds. It turns out there IS such a thing as too much of a good thing—I found that I was having to fill up my bird feeders once a day because the blackbirds were happily popping over from the bullrushes to feast. They will happily eat anything that is accessible, and they have a voracious appetite. I finally achieved a semblance of balance when I figured out what size chicken wire was enough to keep the blackbirds out, but let the towhees in (they’re pretty close in size). Notwithstanding the fact that my feeders all look like tiny little bird prisons now, and the smaller females and young birds are able to get in, I’m happy with the status quo.

Song Sparrow

Melospiza melodia

The Song sparrow is a very plain looking bird with two wonderful features—they like to eat spiders and bugs, and they have a beautiful song. That, as they say, is good enough for me.

From Wikipedia:

Singing itself consists of a combination of repeated notes, quickly passing isolated notes, and trills. The songs are very crisp, clear, and precise, making them easily distinguishable by human ears. A particular song is determined not only by pitch and rhythm but also by the timbre of the trills. Although one bird will know many songs—as many as 20 different tunes with as many as 1000 improvised variations on the basic theme,[citation needed]—unlike thrushes, the song sparrow usually repeats the same song many times before switching to a different song.

Song sparrows typically learn their songs from a handful of other birds that have neighboring territories. They are most likely to learn songs that are shared between these neighbors. Ultimately, they will choose a territory close to or replacing the birds that they have learned from. This allows the song sparrows to address their neighbors with songs shared with those neighbors. It has been demonstrated that song sparrows are able to distinguish neighbors from strangers on the basis of song, and also that females are able to distinguish (and prefer) their mate’s songs from those of other neighboring birds, and they prefer songs of neighboring birds to those of strangers[11].

Trumpeter Swans

Cygnus buccinator

These swans are welcome visitors to our island in the fall, winter, and spring, migrating much further north in the summer for their breeding season. They, along with many ducks and other waterfowl, call the often-unfrozen waters of Vancouver Island home at the southern terminus of their migration, which is a wonderful feature of life on the island—there are often just as many migrant species here in the winter as in the summer, compared to the quiet winter forests and lakes of the rest of the country. My favourite part of hosting these birds on my pond in the winter is their tendency to keep together in large groups and ‘dance’ with one another—heads bopping along to a beat only they can hear.

From Wikipedia:

The trumpeter swan (Cygnus buccinator) is a species of swan found in North America. The heaviest living bird native to North America, it is also the largest extant species of waterfowl with a wingspan that may exceed 10 ft (3.0 m).[2] It is the American counterpart and a close relative of the whooper swan (Cygnus cygnus) of Eurasia, and even has been considered the same species by some authorities.[3] By 1933, fewer than 70 wild trumpeters were known to exist, and extinction seemed imminent, until aerial surveys discovered a Pacific population of several thousand trumpeters around Alaska’s Copper River.[4] Careful reintroductions by wildlife agencies and the Trumpeter Swan Society gradually restored the North American wild population to over 46,000 birds by 2010.[5]

Spotted Towhee

Pipilo maculatus

The Spotted towhee is most notable for its bright red eyes, but the rest of it is almost as striking. They’re a very common feeder species in our neck of the woods—in the winter months to only birds more common than the towhee at my sunflower seed feeders are the house finches. They have a very inquisitive sounding call that almost sounds like they’re asking a question.

From Wikipedia:

The spotted towhee is a large New World sparrow, roughly the same size as a Robin. It has a long, dark fan shaped tail with white corners on the end. They have a round body (similar to New World sparrows) with bright red eyes and dull pink legs. The spotted towhee is between 17 cm (6.7 in) and 21 cm (8.3 in) long, and weighs in at between 33 g (1.2 oz) and 49 g (1.7 oz).[3]

Adult males have a generally darker head, upper body and tail with a white belly, rufoussides and white spots on the their back and white wing bars. Females look similar but are dark brown and grey instead of black. The spotted towhee has white spots on its primary and secondary feathers, the Eastern towhee is the same bird in terms of its size and structure but does not have white spots.[3]

Steller’s Jay

Cyanocitta stelleri

These birds are characters of the first order—like many jays, they’re curious and entertaining to watch. They tend to summer high in the mountains, which means that we tend to see them in the fall and winter, when they drop to the lower elevations seeking food. If it’s a good year for pinecones in the montane areas, though, they might not show up at all.

From Wikipedia:

The Steller’s jay (Cyanocitta stelleri) is a jay native to western North America, closely related to the blue jay found in the rest of the continent, but with a black head and upper body. It is also known as the long-crested jay, mountain jay, and pine jay. It is the only crested jay west of the Rocky Mountains.

Steller’s jay shows a great deal of regional variation throughout its range.[2]Blackish-brown-headed birds from the north gradually become bluer-headed farther south. The Steller’s jay has a more slender bill and longer legs than the blue jay and has a much more pronounced crest. It is also somewhat larger.

The head is blackish-brown, black, or dark blue, depending on the latitude of the bird, with lighter streaks on the forehead. This dark coloring gives way from the shoulders and lower breast to silvery blue. The primaries and tail are a rich blue with darker barring. Birds in the eastern part of its range along the Great Divide have white markings on the head, especially over the eyes; birds further west have light blue markers and birds in the far west along the Pacific Coast have small, very faint, or no white or light markings at all.

Swainson’s Thrush

Catharus ustulatus

The Swainson’s thrush makes one of my favourite calls, commonly heard in late spring and early summer as the sun is setting and the air is cooling (although you do hear the same call during the day, it’s competing with far more bird calls for your attention—at dusk, they stand alone). I’ve spent long periods of time seeking to photograph a bird I hear calling in a nearby tree or bush, only to give up in frustration when this reclusive thrush keeps deep in its hiding place. They’re fairly common in our area, though, as you can tell from the preponderance of its calls as the sun sets.

From Wikipedia:

The breeding habitat of Swainson’s thrush is coniferous woods with dense undergrowth across Canada, Alaska, and the northern United States; also, deciduous wooded areas on the Pacific coast of North America.

These birds migrate to southern Mexico and as far south as Argentina. The coastal subspecies migrate down the Pacific coast of North America and winter from Mexico to Costa Rica, whereas the continental birds migrate eastwards within North America (a substantial detour) and then travel southwards via Florida to winter from Panama to Bolivia.

Varied Thrush

Ixoreus naevius

The varied thrust is largely a forest bird, and I’ve only ever seen them out in the open in our winter months. They’re absolutely beautiful birds, though, about the same size as the American robin. With their distinct orange colours, there’s no mistaking one when you see it.

From Wikipedia:

“The varied thrush breeds in western North America from Alaska to northern California. It is migratory, with northern breeders moving south within or somewhat beyond the breeding range. Other populations may only move altitudinally. This species is an improbable transatlantic vagrant, but there is an accepted western Europeanrecord in Great Britain in 1982.[10]

Nests in Alaska, Yukon Territory, and mountains in British Columbia, Washington, and Oregon. Prefers moist conifer forest. Most common in dense, older conifer forests in high elevations. Moves to lower elevations during the winter where it is often seen in towns and orchards and thickets, or migrates to California. Seen in flocks during winter of up to 20 birds. It is well known for individual birds to fly eastward in winter, showing up in just about any state, then returning to the west coast for breeding.”

Virginia Rail

Rallus limicola

The rail is a bird commonly heard, but not seen. I’ve gotten lucky twice—both times while occupying the lawn chair I set up on a platform I built on a tree overhanging our pond, and reading quietly for tens of minutes and then noticing subtle motion incidentally out of the corner of my eye. They’re secretive, but their loud chuckles as the sun sets are pretty distinct.

From Wikipedia:

The Virginia rail (Rallus limicola) is a small waterbird, of the family Rallidae. These birds remain fairly common despite continuing loss of habitat, but are secretive by nature and more often heard than seen.[2] They are also considered a game species in some provinces and states, though rarely hunted.[3] The Ecuadorian rail is often considered a subspecies, but some taxonomic authorities consider it distinct.

White-Crowned Sparrow

Zonotrichia leucophrys

As promised above, I have very little to add to Wikipedia‘s short description:

The white-crowned sparrow (Zonotrichia leucophrys) is a species of passerine bird native to North America. A medium-sized member of the American sparrow family, this species is marked by a grey face and black and white streaking on the upper head. It breeds in brushy areas in the taiga and tundra of the northernmost parts of the continent and in the Rocky Mountains and Pacific coast. While southerly populations in the Rocky Mountains and coast are largely resident, the breeding populations of the northerly part of its range are migratory and can be found as wintering or passage visitors through most of North America south to central Mexico.

Yellow-Rumped Warbler

Setophaga auduboni

From Wikipedia:

The Audubon’s warbler (Setophaga auduboni or Setophaga coronata auduboni) is a small New World warbler.

This passerine bird was long known to be closely related to its eastern counterpart, the myrtle warbler, and at various times the two forms have been classed as separate species or grouped as the yellow-rumped warbler, Setophaga coronata. The two forms probably diverged when the eastern and western populations were separated in the last ice age.

In North America, the discovery of a hybrid zone between the two forms in western Canada led the American Ornithologists’ Union in 1973 to recognize them as a single species.[1]

Audubon’s warbler has a westerly distribution. It breeds in much of western Canada, the western United States, and into Mexico. It is migratory, wintering from the southern parts of the breeding range into western Central America.

The summer male Audubon’s warbler has a slate blue back, and yellow crown, rump and flank patch. It has white tail patches, and the breast is streaked black. The female has a similar pattern, but the back is brown, as are the breast streaks.

This form is distinguished from the myrtle warbler by its lack of a whitish eyestripe, its yellow throat, and concolorous cheek patch.

The breeding habitat is a variety of coniferous and mixed woodland. Audubon’s warblers nest in a tree, laying four or five eggs in a cup nest.

These birds are insectivorous, but will readily take berries in winter, when they form small flocks.

The song is a simple trill. The call is a hard check.

Many thanks to Ian Reilly for assembling this great collection!

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is a great post! Thanks!

Although I noted that the audio associated with the Varied Thrush (which I have always called a “Party Bird” until I was able to match the song with the bird) is actually a “call”. Their song sounds much different (and why I call them a “Party Bird”). Perhaps you can add that audio to the post? Here’s a description of both & a citation link:

Source: https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Varied_Thrush/sounds#

LikeLiked by 1 person

Saw a few birds near the shore on grass – very like robin in size (maybe slightly smaller) hopping – robin-like but all white underside and darker top perhaps a white bar on or near the eye. What did I see?

LikeLike

That’s a challenging diagnosis…especially given proximity to the shore. I would recommend joining a birding group on Facebook (I belong to several) and asking there—they are full of people with far more experience than I!

My best personal guess would be a spotted towhee…they can have white bellies, are the size of but darker than robins, and tend to hop around on the ground individually and in groups.

LikeLike

Sorry your friends killed the bird trying to survive in the chimney. There must have been a better way…..

LikeLike

Thank you for this. I enjoyed the sound clips as well. I often hear birds too far away to identify.

LikeLike

This is fantastic! Not only am I better informed about local birds, I got many a chuckle, too.

Thank you very much.

😀

LikeLike

This is a wonderful resource. Thank you.

LikeLike

Thanks so much for this!

LikeLike

Lovely reference. Please note the spelling of Steller’s Jay, named for Georg Wilhelm Steller. Yes it is a stellar bird, but that is not its name

LikeLike

Not a Barred Owl, which is brown and pitch black eyes. Perhaps a Western Screech Owl

LikeLike

Hello! I’ve been following your site for a long time now and finally got the bravery to go ahead and give you a shout out from Humble Texas! Just wanted to mention keep up the great work!

LikeLike

I could not refrain from commenting. Exceptionally well written!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Is there a way for me to show images of birds at Neck Point so your people can identify them before I post to Instagram?

LikeLike

Alas no – we’re not set up for that. Why not just post them, and ask people to chime in – make it a challenge to see who can identify it? That way you can have a chuckle, and learn what each one is! 🙂

LikeLike

John – Sure, just not here on the blog. You can join & post your photos in the Yellowpoint Ecological Society Facebook group & ask for help identifying them before you post them to your IG account!

Here’s the link: https://www.facebook.com/groups/722219994619518/

I hope that helps!

LikeLike

Fantastic blog you have here but I was wanting to know if you knew of any discussion boards that cover the same topics discussed in this article? I’d really like to be a part of online community where I can get feedback from other experienced people that share the same interest. If you have any suggestions, please let me know. Kudos!

LikeLike

Thank you for your dedication. Wonderful descriptions and vocals.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I really appreciate this post. I have been looking everywhere for this! Thank goodness I found it on Bing. You’ve made my day! Thanks again

LikeLike

I found this site quite by accident and am DELIGHTED! Your photographs are superb! What you have offered us is so much more than many sites which are funded and organized. So, THANK YOU for gathering all of this wonderful information, data, photographs, and for your charming stories, references, links and cross references too. Just…THANK YOU !!! (I now have to share your site with friends who are going to love it too!)

LikeLike

Thanks for the feedback! We had a volunteer put it together who is a local birds enthusiast. 🙂

LikeLike

Just happened upon this site after I walked along the seashore at Royston. I was thrilled to find -and identify a spotted towhee.

A great resource! Thank you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Lovely. Makes me wish I were back on Vancouver Island now—I’m in Ottawa.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I wanted to thank you for this wonderful read!! I definitely enjoyed every little bit of it. I’ve got you bookmarked to check out new stuff you post…

LikeLike

Thank you! I was trying to identify the “Swainson’s Thrush”, and wishing there was a “shazam” for birds haha!

But you helped me find it 😊

LikeLike

This is an amazing post! It is so wonderful to be able to connect local birds with their songs. I’ve had a favourite bird call for years with no idea on how to identify the bird. Every evening this past week I’ve been hearing it often. Tonight I was determined to discover what bird this is and what it looks like, and I found it here… a Swainson’s Thrush! THANK YOU, THANK YOU, I am delighted beyond words….cheers!

LikeLike

Me as well! The Swainson’s Thrush’s call takes me right back to summer nights at Shuswap Lake where I spent every summer of my youth through the 70s and 80s. That sound IS a summer evening to me, and I have not known until today which bird made it. It has always sounded melancholy and wistful to me. I just love it – my favourite bird call. Thank you so much!

LikeLiked by 1 person

You have given us a handy, and humourous, resource for reference, for which I thank you very much.

Here in Courtenay I am somewhat disappointed in the call of the towhee. It’s a quick ‘ch-we’ sound, which bears very little resemblance to the call that gave it its name. On Salt Spring Island I used to hear something more like “tch0hh-wee” – extended. (Onomatopoeia is always a compromise). That’s more like!

Come spring as I walk my neighbourhood, I get warned off by what I thought were starlings. Someone more knowledgeable than me said they are Brewer’s blackbirds. Pretty bird (so is the starling, despite its bad rap. Don’t they rate a mention?), a tad bigger than starlings however, nice blue tints.

There’s one more bird I’m curious about, mainly because it only seems to be around in cold and snowy weather. It has dark flecks on its yellowish breast, is about the size of a robin, and seems to gather in flocks to devour all the berries on our pyracanthas in 2 days before heading off to the next feed. Hmm. Varied thrush maybe, although its colours are muted compared to your photo? Or some vagrant passing through?

Once again, thankyou…

LikeLike

Googling “vancouver island small brown variegated bird” brought me here. As it happens, I’m staying at my mother’s. She also lives in Yellowpoint and overlooks a pond with a beaver lodge. I could not have found a more local guide!

LikeLike